By Woody Weingarten

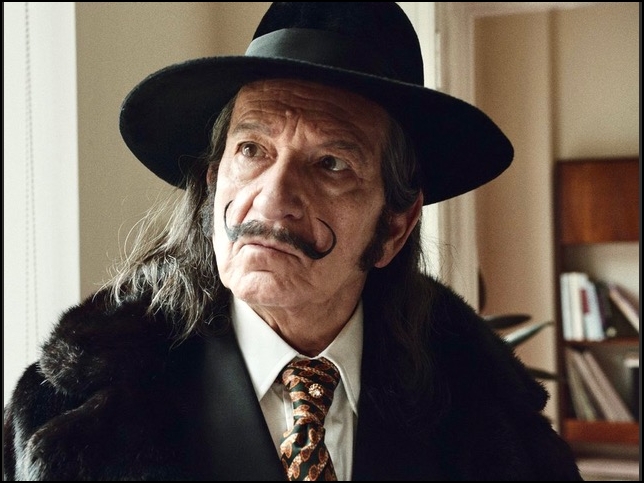

Sir Ben Kingsley, as Salvador Dalí, portrays crazy rather well.

Kingsley also alternates Dalí’s comic and tormented turns rather well. In fact, the actor plays all the famed Spanish surrealist artist’s extreme aspects rather well in the new movie Dalíland. Without making a caricature of him.

Yet, arguably, a smidgeon over the top.

The film’s focus is on Dalí’s final years, when his octogenarian relationship with his older, tyrannical wife and muse, Gala, is disintegrating because, as one character contends, they no longer like being with one another since it reminds them “that they’re old.”

Gala, in fact, is constantly chasing her youth by bedding down with one of her boy toys, the latest being the actor then starring in the lead role of Broadway’s Jesus Christ Superstar.

Dalí, meanwhile, is relegated to voyeurism, which he apparently prefers anyway.

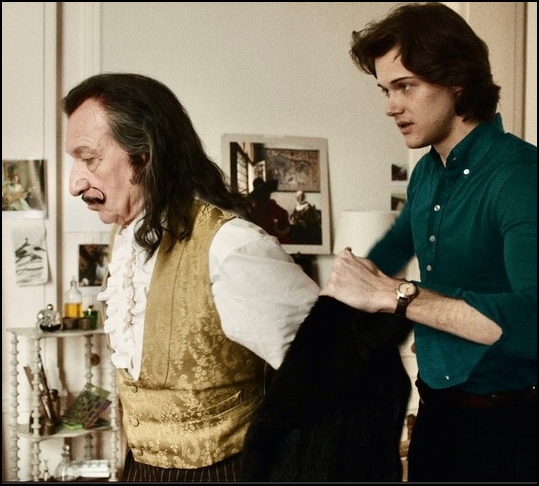

The movie’s point of view stems from neither Dalí nor Gala, though — we see the one-of-a-kind genius through the eyes of James, a Dalí acolyte-sycophant then fighting to un-immerse himself from the artist’s destructive lifestyle filled with ostentatious fame, bizarre parties, and erotica.

Canadian director Mary Harron starts Dalíland with an astute bit of character self-assassination, a clip of Dalí’s hysterically funny appearance on the TV game show What’s My Line? in which he answers every question with a “yes” even if it’s totally inappropriate and must be corrected by emcee John Daly. When Dalí answers affirmatively about being a leading man, panelist-columnist Dorothy Kilgallen smoothly chastises him with the comment, “He’s a misleading man.”

That stands as a touch of foreshadowing to a deep dive into the artist’s darker aspects — to wit, the scene quickly shifts to a party in which Dalí focuses on Amanda Lear, a trans, and Alice Cooper, a friend.

Harron may have been a superb choice for the biopic. Her work-life began as a punk music journalist, immediately integrating oddball characters into her sphere of influence. In 1996, her first feature film, I Shot Andy Warhol, depicted a wannabe assassin as a feminist hero. She also directed The Notorious Bettie Page, about the famous nude pinup subject.

Kingsley, of course, won a best actor Oscar for his title role in 1982’s Gandhi.

In Dalíland, the artist doesn’t come off as the least bit likeable. Rather, he’s annoyingly egocentric (“I do not compare myself to God,” he pontificates. “Dalí is almost God”) and self-indulgent (he rents space at the St. Regis Hotel in New York City at $20,000 a month).

And he doesn’t blink at the knowledge that endless prints of his works are criminally being peddled at extraordinary prices as lithographs.

The main weakness of the low-budget, 1 hour, 43-minute film is the absence of the artist’s paintings (the producers clearly couldn’t afford reproduction rights). A second flaw is an overall lack of tension. And although the costumes are effective (especially Dali’s long, ornate dressing gowns and vests that look as if they’d been replicated from an 18th century operetta), and despite a hand-held camera frantically scooting here and there during frenzied party scenes, Kingsley’s man-of-many-faces performance is so melodramatic everything else fades into near-nothingness.

Still, considering the impossibility of accurately depicting a mad, alluring, repulsive womanizer in a story that’s not unlike watching a train about to derail, screenplay writer John C. Walsh, director Harron, and Kingsley do admirably well.

A pair of flashbacks, intended to lay the groundwork for the artist’s later behavior patterns, ironically feature Ezra Miller, who identifies as non-binary and who’s faced a series of disorderly conduct and assault charges and been treated for “complex mental health issues.”

But perhaps the strongest image in the Magnolia Pictures-distributed film — which is set in Spain and New York during the mid-1970s — is when Dalí talks of a mountain peak that “appears in my painting The Great Masturbator” and remembers that “this is where [Gala] asked me to kill her, you know.”

A second memorable cinematic moment shows the artist asking James to bring him “many beautiful asses,” followed by his having the girls dip their rumps into paint and press them onto paper so he can instantly convert the images into saleable “art.”

Everything in Dali’s mind, in fact, becomes art — even his dyed, waxed handlebar mustache, which is treated as if it’s a priceless sculpture.

My own favorite moment is the chunk of a flashback where Dali wildly waves his cane as if conducting a distorted symphony of life, seemingly a summation of what his essence really is.

A personal note: Because I greatly admired Dali’s imagination and groundbreaking work when I was young, I paid $1,200 for an early lithograph — despite my being unsure at the time that lithos were truly art, and despite my being only 93.7 percent certain that the “certificate of authenticity” was actually authentic. Dalíland not only brought back a vision of that transaction but of the artist’s most famous work, The Persistence of Memory, and my own memory-regret that my ex-wife ended up with the extremely valuable litho.

-30-

ASR Senior Contributor Woody Weingarten has decades of experience writing arts and entertainment reviews and features. A member of the San Francisco Bay Area Theatre Critics Circle, he is the author of three books, The Roving I; Grampy and His Fairyzona Playmates; and Rollercoaster: How a Man Can Survive His Partner’s Breast Cancer. Contact: voodee@sbcglobal.net or https://woodyweingarten.com or http://www.vitalitypress.com/

ASR Senior Contributor Woody Weingarten has decades of experience writing arts and entertainment reviews and features. A member of the San Francisco Bay Area Theatre Critics Circle, he is the author of three books, The Roving I; Grampy and His Fairyzona Playmates; and Rollercoaster: How a Man Can Survive His Partner’s Breast Cancer. Contact: voodee@sbcglobal.net or https://woodyweingarten.com or http://www.vitalitypress.com/

| Title | Daliland |

|---|---|

| Directed by | Mary Harron |

| Screenplay by | John Walsh |

| Distributing Company | Magnolia |

| Production Date | Opens June 9th |

| Runtime | 1 hr 56 min |

| Showing | Landmark’s Opera Plaza Cinema, 601 Van Ness Ave., San Francisco; Rialto Cinemas Elmwood, 2966 College Ave, Berkeley; Century Regency, 280 Smith Ranch Road, San Rafael. |

| Reviewer Score | Max in each category is 5/5 |

| Overall | 4/5 |

| Performance | 4.5/5 |

| Script | 3.5/5 |

| Aisle Seat Review PICK? | YES! |